Bryce Canyon Travel Guide

The smallest member of Utah’s “mighty five”, out-of-the-way Bryce Canyon is home to some of the strangest geology in the United States. Technically not even a canyon, Bryce Canyon’s colorful hoodoos are a striking testament to the artistic forces of Mother Nature. This Bryce Canyon travel guide covers everything you need to plan a visit to the national park.

I first visited Bryce Canyon during a family road trip back in the mid-90s and recently returned for a two-day visit as part of a long road trip in the American Southwest. This Bryce Canyon travel guide is based on extensive research and my experience.

Why Visit Bryce Canyon?

The natural forces of erosion seem to work at high speed in Bryce Canyon. Extreme overnight temperatures meet the morning sun and sculpt the reddish limestone into peculiar pillars like nowhere else.

With over 65 miles of trails, every hiker can find a suitable way to get to know Bryce Canyon on foot. Easy rim trails offer solitude from the busy viewpoints, but for the best experience, descend to the Bryce Amphitheater floor to really get to know the hoodoos.

Bryce Canyon is small and adequately explored on a one-day visit that combines scenic viewpoints and short hikes. Overnighting around Bryce is a memorable stop on any Southern Utah road trip.

Several sections make up this travel guide:

Additional Southern Utah Resources

Check out additional travel guides to Southern Utah and combine your visit to Bryce Canyon with additional members of Utah’s “Mighty Five”.

Background

Bryce Canyon National Park is one of Utah’s “Mighty Five” national parks. However, due to its relatively small size and remote location, Bryce Canyon does not experience the same visitor numbers as some of the more popular members of this scenic club, such as Zion or Arches National Park.

From a geological perspective, Bryce Canyon sits at a high elevation at the edge of the Paunsaugunt Plateau, which is part of the Colorado Plateau. Bryce Canyon was not formed by erosion but rather from a different natural force that created large crescent-shaped amphitheaters at the very edge of the plateau. Therefore, Bryce Canyon is not technically a canyon. The most famous section of the “canyon” is the Bryce Amphitheater, the largest natural depression within the national park.

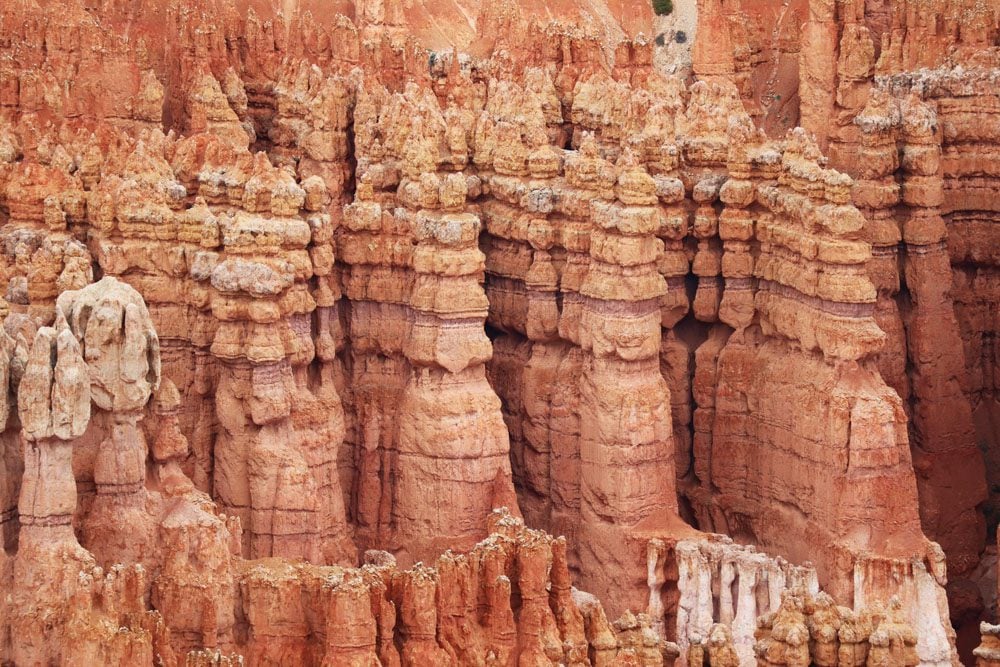

The unique geological forces that created Bryce Canyon are still at work and are responsible for the bizarre limestone pinnacles of red, yellow, and orange known as hoodoos. From the edge of the rim, visitors marvel at the colorful layers of Bryce Canyon’s sediment, punctured by thousands of hoodoos, some of which rise to a height of up to 200 feet (60m). The hoodoos are constantly shaped by the extreme temperature fluctuations between night and day. During the freezing nights, ice expands inside small cavities. Then, as it melts during the daytime, it chips away at the soft rock.

Hoodoos form when they completely detach from their surroundings. Before reaching “adulthood”, neighboring pinnacles form windows, while yet-to-be-punctured younger limestone forms the canyon wall (rim).

The Bryce Canyon area was settled thousands of years ago by Native American tribes who came and went with the changing climate. In the 1850s, Mormons arrived in the area looking for agricultural land to grow crops and cattle. In the 1870s, Ebenezer Bryce built his homestead in the Bryce Amphitheater area, for which the “canyon” is named. In 1923, Bryce Canyon was designated as a national monument. Its status was upgraded to a national park in 1928.