The Mystery Islands of Polynesia

Mutiny on the Bounty

Bidding farewell to the Gambier islands also marks our official farewell to French Polynesia. The captain now shifts into high gear and begins the journey to the next stop – Pitcairn Island. The increased velocity is well felt in the stomach and the reason for this will be uncovered in about two days. At night, we change the clocks forward, a ritual that will repeat itself several times, further demonstrating the vast distances we are covering.

Pitcairn Island is 1,400 miles southeast of Tahiti and 1,200 miles west of Easter Island. During the 12th century AD, Pitcairn was likely settled by Polynesians from Mangareva. They traded with the prosperous kingdom until its collapse, a collapse that caused the tiny native population on Pitcairn to perish.

With a surface area of just 4.5 km², Pitcairn is swallowed by the vastness of the ocean and is easy to miss. This feature is precisely what attracted the Bounty mutineers upon arrival on the uninhabited island in 1790. Nine months have passed since the daring rebellion against the tyrannical Captain William Bligh. The mission to carry breadfruit from Tahiti to the Caribbean slave colonies ended badly for Bligh. After months of waiting in Tahiti, his crew is in love with the Polynesian way of life and is in no hurry to return to the high seas. Their new leader, Fletcher Christian, finds Pitcairn completely by chance, and nine British sailors and eighteen Polynesian men and women establish a community that goes on to live in complete isolation for the next 18 years.

Over the following centuries, countless books and articles have been written about the famous mutiny and its aftermath, and Hollywood has even devoted five films starring its finest stars. The descendants of the mutineers still reside in Pitcairn and their presence is the necessary excuse for the journey to such an isolated point, even by Polynesian standards.

We arrive at Pitcairn a day before the original plan and are in Bounty Bay by a mother humpback whale and her newborn calf. Mother Nature has graciously created a narrow window of opportunity for us to land on the island with Zodiac boats and our captain recognized this in Mangareva. With unpredictable weather and in the absence of a harbor, many of the few who reach the shores of Pitcairn will never set foot on the remote island. There is a tense feeling among passengers on deck and the only question on everyone’s mind is, “will the captain give the green light to make landfall?”

To ease the tension, we chat with Pitcairn resident Simon Young who has just boarded the ship as a representative of both the border police and the Ministry of Tourism. Young tells us about life on the remote island which currently numbers only 42 souls, most of whom are part-time civil servants. The island is visited by a cargo ship from New Zealand every three months and just like the tourists, all goods must be ferried to the island in small boats. “We grow everything here, such as taro, banana, and breadfruit, but whatever nature cannot provide we must import from outside.”

With a stroke of luck, the green light is given and we make our way into Bounty Bay as waves smash into the rugged coastline. On the wharf, we must now conquer the “Hill of Difficulty”. This legendary path is the only way to reach the fertile plateau and the only settlement on Pitcairn – Adamstown, named after John Adams, the last mutineer to survive a bloody civil war. There is a bizarre feeling on Pitcairn, a combination of surreal natural beauty and a sense of accomplishment. All the books, movies and thoughts blend into a half-day visit before the weather turns sour.

On the way to the center of the village, locals on quad bikes pass by. Even the island’s sole police officer helps passengers overcome the steep incline. Following the highly publicized sexual assault trial in 2004 that threatened the very existence of the settlement on Pitcairn, there is a permanent police presence on the remote British territory.

It’s a busy day in Adamstown. The entire local population is on hand with an improvised market erected in the village square. Collectible stamps, wooden models of the Bounty, locally-produced honey, and other memorabilia are all for sale and any currency is welcomed. Around the square stands the small Adventist church, the community hall, and post office, but the star attraction is the anchor of the Bounty, salvaged from the depths in 1957.

On the outskirts of the village, banyan trees mark the way to the local school, whose current roster of two students is outnumbered by toilet stalls. Towering above is the cliff that houses “Fletcher Christian’s Cave”. It is said that the leader of the mutiny spent many solitary hours gazing into the endless horizon, perhaps out of fear of being caught and brought to trial by the British Crown or perhaps out of longing for loved ones never to be seen again.

Pitcairn is a paradise for nature lovers and, as it turns out, for quad bike enthusiasts as well. The island is irrationally crisscrossed by dirt paths that also reveal Pitcairn’s fertile soil. As I hike to another spectacular vista, I meet the island’s doctor who turns out to be the police officer’s husband. He mentions that most of his time is devoid of action and that is a good thing because, in urgent cases, it is better to pray than to wait for evacuation. “This place is a paradise for those who can adapt to its simple way of life and sense of community but, with only two residents between the ages of 18-30, the future of the settlement is unclear.”

At the summit overlooking Bounty Bay and Adamstown, the doc and I are trying to locate the remains of the Bounty which the mutineers burned upon arrival. Rumor has it that, on a good day, you can spot the wreckage from up here, but today is not one of those days. With Zodiacs sailing in one direction, our ship is preparing for departure. The time has come to descend the Hill of Difficulty and restore Pitcairn to its natural state as a lonely paradise.

The Edge of the Triangle

Our talented captain awaits on board with a great sense of relief that is hard to miss. He is now free to embark on the last leg of this journey, 2,100 miles or three days of sailing to Easter Island. We cross more and more time zones and sail on starless nights. How the ancient Polynesians sailed these lonely waters more than 1,000 years ago is incomprehensible, precisely the reason for Norwegian researcher Thor Heyerdahl’s theory of a South American origin to Easter Island. In 1947, he set out on a well-publicized journey to prove his theory on board the Kon-Tiki.

Easter Island marks the eastern boundary of the Polynesian Triangle. The triangular-shaped island was likely settled by Polynesians from Mangareva who may have lived in complete isolation from the moment they arrived until re-discovery on Easter Sunday in 1722. This remote land is shrouded in mystery and filled with theories, including some implying an extraterrestrial connection. About 300 religious platforms known as ahu and close to 1,000 stone statues known as moai are scattered throughout the island, averaging 5 tons in weight and some towering over 30 feet in height.

These monolithic giants are evidence of an obsessive competition between rival tribes that exploited the island’s already limited natural resources. Competition and food shortage led to a civil war that included cannibalism and the toppling of all moai statues. In the following decades, diseases brought by European visitors and slave-raiding expeditions decimated the remaining native population. The few who survived forgot their ancient religion and lived in abject poverty.

The rising sun above the horizon reveals a distant landmass and raises smiles on the faces of passengers who have seen nothing but water for the last three days. This joy surely must have engulfed the fragile outrigger canoes of the brave Polynesian pioneers on this very same course. We anchor near the capital Hanga Roa – population about 7,000, all Chilean citizens (some to their dismay) and half of whom are native Rapanui. The landscape is strange, more Ireland than Polynesia. The impressive peaks and rainforests to which we had grown accustomed have been completely replaced here by barren hills, further testimony to the “life of luxury” that preceded the great collapse.

A Celebration for the Eyes, a Challenge for the Soul

Most of the island is part of a national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. We begin the quest for uncovering the secrets of Rapa Nui in temples where moai statues were strategically placed in points bearing astronomical significance. When examining the statues from up close, the concrete archeologists used to bond the heads to the bodies are clear signs of inter-tribal violence. This is evidence of the destruction of temples that characterized the civil war which took place when the island’s original religion began to collapse. In response to the constant violence and food shortages, tribes developed a new religion centered around a new god and the bird which represented him on earth. Every year, rival clans would gather in a small village on the edge of the Rano Kau volcano – our next stop.

The volcanic crater of Rano Kau is the most impressive natural feature on Easter Island. Thanks to a diameter spanning nearly a mile wide and a depth of over 650 feet, its crater doubles as a freshwater lake with a unique ecological system in which reeds flourish. Sediment samples taken from its muddy bottom yielded the discovery of many species of prehistoric vegetation and possibly evidence of native palm trees that once covered the island.

At the edge of the crater, we walk along a path that leads between the circular stone houses of the abandoned village of Orongo. Until the 1860s, island tribes would gather in Orongo for the strange Birdman competition in which a tribe’s athletic representative would swim across a mile of shark-infested waters and scale an isolated cliff and wait for the first-laid egg of the sooty tern bird. The victorious chief was awarded the title of “Birdman” and, as representative of the (new) god Make Make, got to call the shots on Easter Island for a full year.

From one crater to the next, we visit Rano Raraku in the center of the island. Better known as “the quarry”, it is the source of 95% of the island’s nearly 1,000 moai statues. After completion, members of the sculpting tribe would carefully lower the finished statue to the bottom of the hill. If not broken on the way down, the moai would then be transported via a network of roads to its designated ahu, perhaps in a standing position as the legend tells.

Wandering among the unfinished statues left behind is a chilling experience. Some are buried neck-deep, their heads with an expression frozen in time. Some were clearly broken on the way down and must have caused great hardship to the tribe. Some were simply left unfinished. The largest of them is known as “The Giant”, a monolithic monster equal in height to a five-story building and in weight to two Boeing 737s. What fueled this out-of-control sculpting frenzy and what was the feeling like during the “last shift” before the quarry was abandoned?

We conclude our tour of Easter Island and the entire journey on a high note. The Tongariki temple is near the “factory shop” – the moai quarry we have just visited. This is the most impressive temple in the Polynesian Triangle and its monumental platform is adorned by a row of 15 giant Moai statues, all gazing in traditional fashion towards the interior of the island. It is difficult to fathom how an ancient primitive culture created what our eyes are seeing, but it is easy to understand why this impressive backdrop is most often used to advertise this mysterious destination.

The visit to Easter Island and the rest of Polynesia’s “mysterious islands” is not only a celebration for the eyes but also a real challenge for the soul. Can the region’s history tell us anything about our own future? Will the exploitation of natural resources link our future to the fate of the Mangarevan Empire in the best case, or at worst, with that of the Rapanui?

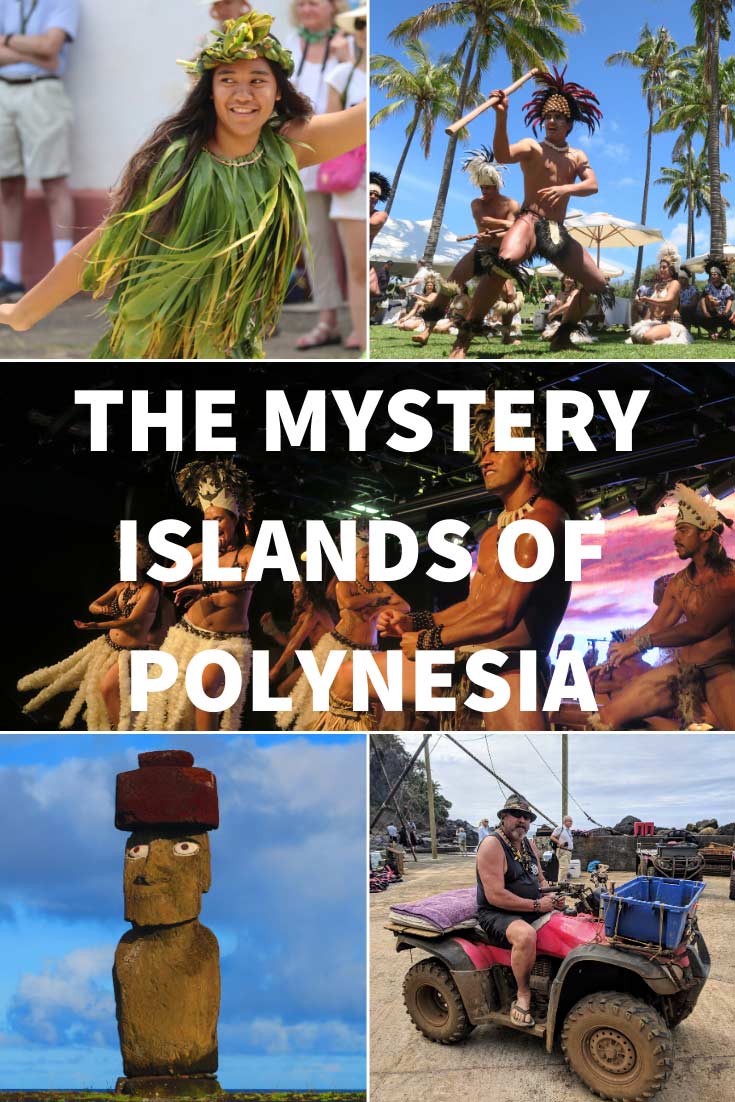

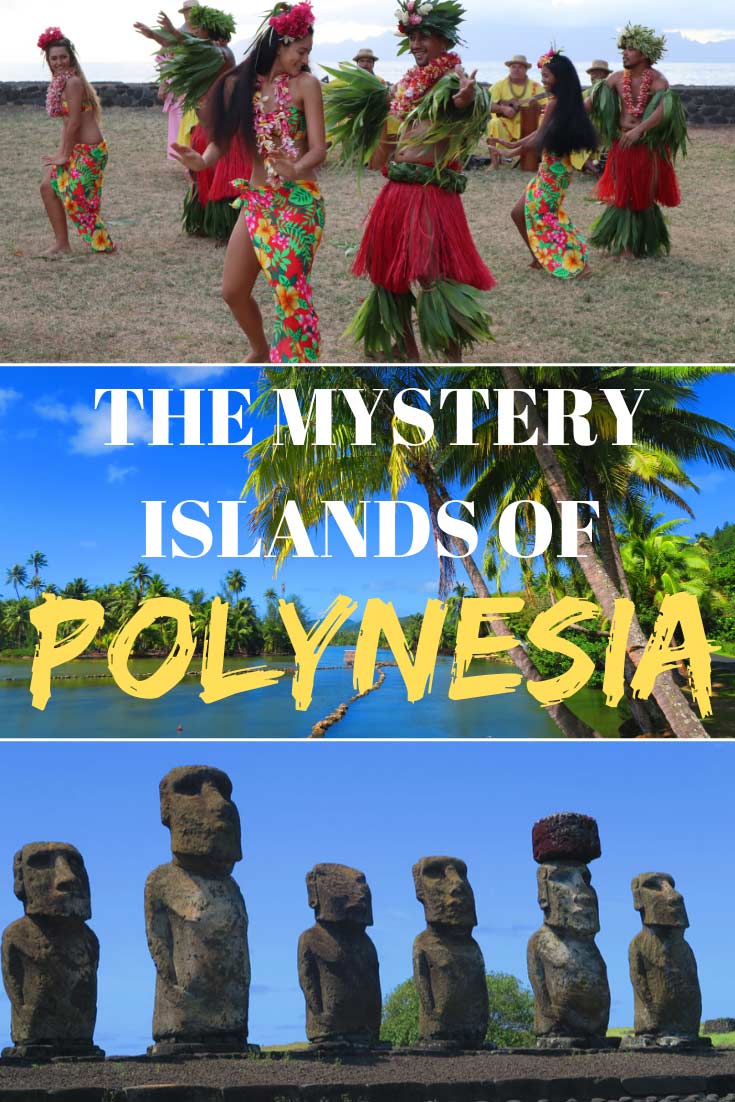

Pin These Images To Your Favorite Boards!

Tahiti, Tailor Made!

The Islands of Tahiti are among the last places to be colonized by mankind, 118 islands, each with its unique personality.

Get expert advice and assistance with planning your trip to the destination where tropical dreams come true!