The Mystery Islands of Polynesia

To one of the most remote places inhabited by humankind and the last outpost to be settled on Earth, this is the story of a 2,817-mile sea voyage to Polynesia’s “Mysterious Islands”. Ancient cultures, exotic dances, bizarre anthropological theories and a tiny community whose status is far greater than its physical size – a journey to the edge of the Polynesian Triangle from Tahiti to Easter Island.

On November 1, 1520, after over a year at sea on a journey that began in Spain, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan is attempting to find a gap through the tip of the South American continent on his way to circumnavigate the planet. The path he chooses, a strait that would later bear his name, is a maze riddled with countless dead ends and plagued by unpredictable currents, relentless winds, heavy fog, and lots of uncertainty.

Tensely navigating through the strait for 38 days, Magellan emerges from the other side and enters the Pacific Ocean, naming it in light of the relatively comfortable weather conditions compared to the difficult weeks that have passed. However, Magellan is unaware of one important detail – the sheer size of the ocean he has just begun to cross.

The Pacific is the largest of the planet’s five oceans, covering about a third of the Earth’s surface. So immense is this body of water that one could fit all continents within its boundaries (in theory, of course) and still have space left for “another Europe”. The infinite blue of the “King of the Oceans” is interrupted on occasion by 1,000 islands that make up the Polynesian Triangle, an area stretching between New Zealand in the west, Hawaii in the north, and Easter Island in the east.

The vast size of the Pacific is an insurmountable obstacle even for today’s experienced seamen, but for the ancient Polynesians, the ocean was viewed as a superhighway. Thanks to their remarkable navigation skills and courage, this obstacle would be conquered down to the very last piece of dry land that appears like a grain of sand on a world map.

Heading to French Polynesia? In-depth island guides to all 5 archipelagos await you, including sample itineraries and essential travel tips & tricks.

Mr. Tahiti

The South Seas journey begins in Tahiti, the beating heart of French Polynesia and the definition of exoticism. The ship that will carry us to Easter Island – the edge of the Polynesian Triangle – is due to arrive in a few days from Samoa in the west, providing an opportunity to adjust to “island time”, a chance to explore this mountainous island so perfectly sculpted by nature and connect with the hospitable Tahitians that call this place home.

Tahiti’s wild interior is devoid of human settlement and the only way to explore it is on a guided 4X4 tour. At the popular surfing village of Papenoo on the east coast, we venture inland and follow the contours of the Papenoo River, the longest in French Polynesia. The river flows through the lush Papenoo Valley, a basin formed by the collapse of a caldera that once topped Tahiti’s volcano. Much of the massive amount of rainfall that falls on the island’s peaks find their way into the valley. Even in the dry season, our jeeps must ford the river and pause for us to admire the cascading waterfalls that drop from the mountain tops, some of which rise to a height of over 2,000 meters.

Before the arrival of the missionaries in the late 18th century, the valley was home to thousands of Tahitians. They left their mark in the form of countless fruit trees and ancient temples, known in Tahiti as marae. As we explore what remains of the marae with our local guides, we can’t help but feel a strong sense of spiritual presence. Polynesians call this mana, the feeling of a supernatural presence that connects man with nature and the heavens. Despite the conversion to Christianity, even to the present day locals frequent these spots and pray to their ancestral spirits.

Before exiting the interior of the island on the west coast, we visit one of Tahiti’s most magical spots. At an elevation of 473 meters, Lake Vaihiria seems to be taken straight out of a tropical fairytale, a peaceful lake perfectly hidden by the emerald peaks awaiting the occasional visitor. In 1791, British troops made the arduous journey to this perfect hiding spot in search of Bounty mutineers from the infamous mutiny.

On the following day, we are greeted at the entrance to the Museum of Tahiti and Her Islands by a duo of ukulele guitars and the broad smiles of Teuai Olivier Lenoir’s local dance group. Lenoir is a living legend in Tahiti, a talented choreographer, a personal friend, and an expert in the local culture. His dance group is coming off a recent win in the annual Heiva Festival, a coveted dance, song, and traditional sports competition between groups from French Polynesia’s five archipelagos held every July.

We rotate between stations manned by muscular men and beautiful young women wearing flowers in their hair. Each station is a kind of lightning workshop for the aspiring wannabe Tahitian. We learn how to prepare day-to-day utensils from the branches of the coconut tree, how to weave necklaces made from heavenly-scented gardenia and how to turn the inside bark of a local tree into fabric known as tapa.

All of a sudden, the sound of beating drums overpower the tropical bird chatter. It is time to gather on the lawn at the edge of the lagoon facing the neighboring island of Moorea and watch a band of exotic dancers casting a hypnotic spell with their sensual moves. The motif of song and dance will accompany us throughout this long voyage. They are inherently part of the Polynesian DNA, the same identity that Christian missionaries sought to erase but which is now an inseparable part of the island culture.

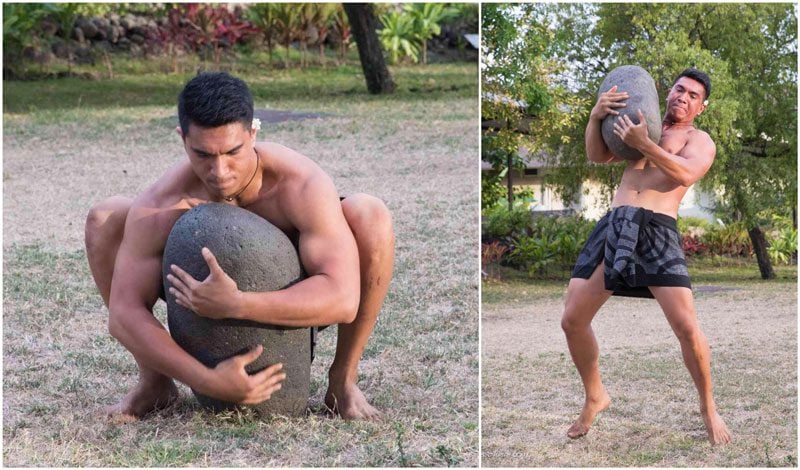

And, if the dancing wasn’t enough to impress the newly arrived popa’as, aspiring “Mr. Tahiti” champions scale a fully-grown coconut tree with lightning speed and, on reaching the ground, hoist a basalt boulder weighing over 200 pounds onto their wide shoulders.

“The connection to our roots, the language, the dance, and the tradition, imparting to our children and sharing our culture with those who visit our islands, are the foundations of our cultural survival”, Lenoir notes.

The Romantic Island

One cannot visit the islands of French Polynesia without paying a visit to the most famous of them all. Bora Bora is blessed with rare beauty, even in a part of the world filled with so many stereotypically tropical wonders. A magnificent high island with its signature peak of Mount Orohena, surrounded by a majestic lagoon with the bluest of waters. What else can you ask for? How about a dreamy resort like the Pearl Beach, with a perfect view of all this beauty…

We head out on a 4X4 tour to reach the island’s best panoramic lookouts to get the best views of this paradise. Bora Bora is without a doubt beautiful, but it likely owes its claim to tourist fame thanks to a very dark period in history. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the United States built a major base on Bora Bora as part of Operation Bobcat. An airstrip was laid (the same one still used today), roads were paved, wells were dug and cannons were positioned to defend the only entrance into the lagoon. Thousands of servicemen spent time in paradise without much action (at least of the military type) and upon their return, the secret of Bora Bora was out. Our tour takes us to the remains of the cannon stations, now rusting away and pointing in the direction of luxury overwater bungalows.

By far, the top highlight in Bora Bora is its lagoon, three times the size of the actual island. I reconnect with Didier, the local multitasking guide who took me on this very same tour back in 2015 (can you believe he’s almost 50?).

Didier first leads us outside the lagoon, where he seems very comfortable with adult lemon sharks. We then head to the coral garden to visit the tropical fish and moray eel, but to my surprise, Didier’s sharp eyes catch a stonefish hiding within the coral, a first for me. We wrap things up with some playful time with stingrays, before enjoying a delicious BBQ lunch on our own private island frequented by birds and baby reef sharks.

Coral Gardens and Nukes

With our biological clocks fully calibrated and with the arrival of our ship – Le Boreal – we are ready to embark on a voyage that will retrace the steps of the most daring ancient Polynesian settlers. There is a complete contrast between the luxury experience that awaits us and the hardships that most likely dominated ancient discovery voyages on outrigger canoes. However, in the absence of commercial flights linking the islands on our route and even the absence of landing strips in some, this is the only way to uncover the secrets of the “mystery islands” of Polynesia.

The first stop is Rangiroa atoll, about 300 miles from Tahiti. Part of the Tuamotu Islands – the world’s largest chain of atolls – Rangiroa is the second-largest atoll in the world, known as “the infinite atoll”. As our ship enters through one of only two openings in the reef, a pod of spinner dolphins comes to greet us, leading the way in front of the ship’s bow.

Image by Morgane Monneret

Rangiroa is a “mecca” for underwater adventurists, and with our ship safely moored, we get the chance to visit “the aquarium”, a snorkeling spot abundant with marine life.

As the sun begins to set, we are accompanied by a local rowing in an outrigger canoe on our way out of the lagoon back to the waters of the Pacific Ocean. The colors of Rangiroa are forever in our hearts and minds, both the dazzling blue of the daytime and the changing shades of gold ahead of nightfall.

From Rangiroa, the captain must now cautiously navigate between the 76 atolls that form the archipelago to our next destination, the Gambier Islands, 870 miles or two days of sailing due east. This route has subdued many seamen over the years, the last of them just a few weeks ago, for these waters hide many coral reefs, and its low-lying atolls lack clear signs of land. Separating us from the ocean floor is 2.5 miles of water but, when the midday sun shines and illuminates the abyss, this distance seems much smaller.

As we near the tip of the chain of atolls, the captain steers as close as possible to Mururoa Atoll, one of the atolls used by the French government for nuclear testing. Between 1963 and 1996, over 150 nuclear tests were conducted in Mururoa and its neighboring atolls. This dark episode in French Polynesia’s history still serves as an open wound. The French government refuses to offer transparency as to what took place and what are the known effects. This is perhaps the reason why the French Navy stationed on Mururoa caution Captain Garcia to stay away from the island which is off-limits to civilians and reporters.

A Tale of a Mad Priest

The Gambier Islands are sometimes referred to as the “forgotten islands.” Due to the great distance from Tahiti, visitors are uncommon, as in the past and the present. Fourteen islands are enclosed by a large lagoon but only about 1,300 inhabitants call this place home, most of whom live on the main island of Mangareva. The pace of life around here barely makes it to second gear and, if it weren’t for its flourishing black pearl industry, the island group might still justify its nickname. However, this isolated archipelago is considered the cradle of Catholicism in Polynesia and bears a fascinating and tragic history marked by a sequence of events whose effects will be felt thousands of miles away.

These isolated islands were likely settled from the Tuamotus in the 10th century AD. Its Polynesian pioneers would go on to establish the mighty Mangarevan Empire, characterized by a rigid hierarchical structure with an omnipotent chief at the top of the social pyramid. Over the years, the kingdom traded with tribes in the Tuamotus, Marquesas Islands, and even with distant Pitcairn Island – our next stop.

With a need to feed a growing population, locals converted forests into agricultural plots – a disastrous move with devastating effects on the island’s environment. Rain fueled soil erosion and the failure of crops. In the absence of mature trees, replenishing canoes for fishing and inter-island trading became impossible and hunger soon followed. Eventually, the kingdom spiraled into a civil war in which cannibalism was part of the game.

Into this vacuum enter missionaries. After the re-discovery of the islands in 1797, a race between English Protestants and French Catholics began. In 1834, the French priest Honore Laval leads a mission to save the savage cannibals. With a surplus of motivation and self-confidence, he wins the hearts of the locals and persuades the chief to convert to Christianity, a move that makes Laval the de facto ruler.

He immediately orders the destruction of temples, introduces a rigid constitution known as the Mangarevan Code and begins the implementation of a megalomaniac and unnecessary construction project of churches, palaces, watchtowers, and religious institutions. Laval’s workforce consists of the subdued local population and funds are raised by taking over the island’s most precious tradable commodity – the black pearl.

The crowning achievement is the Cathedral of Saint-Michel, whose construction cost the lives of hundreds of islanders. Fashioned in Spanish style and made of bricks carved from the coral reef, its altar is adorned with hundreds of exquisite black pearls and magnificent mother-of-pearl shells. Saint-Michel can accommodate 1,200 worshipers, far beyond the demand of the dwindling local population by the inauguration date. Eventually, French authorities in Tahiti woke up and the mad priest was sent packing.

We sail towards Rikitea – the capital of the island of Mangareva. On the way, I recall the accounts of Robert Louis Stevenson from his visit to the island in 1932. At his first glance at the massive cathedral, the author of Treasure Island notes how detached it is from the surrounding virgin landscape. The path to the church and the village square passes through the main street, crowded on both sides with countless colorful hibiscus flowers and trees laden with fruits such as lychee, papaya, mangoes, and oranges.

The dampness inside Laval’s church is suffocating but this doesn’t seem to bother the village women who are busy preparing for an evening ceremony honoring the Virgin Mary. Before we embark on a walking tour among the Laval-era ruins, we catch some shade outside the cathedral under the leafy branches of a huge breadfruit tree and enjoy a traditional Mangarevan dance which freely translates to “foot drumming.” This slow act greatly differs from the sensual Tahitian dancing and is very much in tune with the slow pace of the island.

Black Pearls and White Sand

The Gambier Islands are not known for their tourism figures but rather for their black pearls. Before leaving the archipelago, we visit the island of Aukena. The tiny island is privately owned by Robert Wan, the “father” of the black pearl industry in French Polynesia. Wan’s pearl farm has turned the production of black pearls into a perfectly orchestrated process. One of the local workers takes us through the various working stations and we finally learn how the process works, from an oyster to a pearl in a matter of a few years.

Robert Wan’s black pearl island is also blessed with one of the finest beaches in French Polynesia. After learning about the making of a black pearl, we finally get a few hours to rest and snorkel on this beautiful stretch of tropical paradise.

Continue to the next page for the second part of the return voyage from Tahiti to Easter Island!