Traveling in French Polynesia During COVID: Part 5 – Tubuai & Raivavae

This is the story of a six-week island-hopping journey in French Polynesia during COVID-19. In this post, we continue the voyage across the remote Austral Islands. We’ll start on the fertile island of Tubuai before heading further south to unspoiled Raivavae which is said to resemble the Bora Bora of old.

In the previous post, we swam with humpback whales and explored the caves of Rurutu Island, the first stop on a three-island tour of the Austral Islands. In the fifth part of the series, we continue southeast and stop on the island of Tubuai before wrapping things up in Raivavae.

Heading to French Polynesia? In-depth island guides to all 5 archipelagos await you, including sample itineraries and essential travel tips & tricks.

Tubuai

Pronounced Tupuai, Tubuai is the principal island in the Austral archipelago. With an area of just 45 square km, Tubuai is the largest island in the chain, home to approximately 2,000 residents. Its fertile plains nestled between two mountain ranges are a patchwork of agricultural plots, both for private consumption but mainly for export to the markets in Tahiti. The shores of the main island are dotted by several sandy beaches while Tubuai’s lagoon hosts a few islets (motu) that float at the edge of the coral reef.

Despite its beauty, I originally only planned to stay one night in Tubuai, a sort of a “forced connection” en route to Raivavae. But due to the COVID situation, Air Tahiti changed the flight schedule and I had to spend three nights in Tubuai before being able to continue the journey. As often happens with last-minute changes, this one was also for the better, as I was able to fully explore an island that is seldom on the tourist path.

Island Tour

It was “international tourism day” on the day of my arrival to Tubuai, a festivity that was celebrated in French Polynesia despite the global epidemic. After having our hands sprayed with sanitizing gel before entering the terminal, we were presented with flower necklaces and slices of mango, as a local band was playing what would become the soundtrack of this voyage, a beautiful welcoming tune called Faarii mai na. Normally, there would be dancers accompanying the band but times are different now. I do feel lucky though to be present here at a time when traveling has become only a dream for so many.

I was picked up at the airport by Wilson Doom of the Wipa Lodge. Despite an ominous last name, Wilson is a welcoming man who is passionate about showing his island to visitors. Together with his wife, he runs a superb pension just steps away from a sandy beach that is perfectly positioned for sunsets. After Cyclone Oli devastated Tubuai in 2010, the Dooms relocated their original pension to the present spot.

After settling in, I embarked with the other arriving guests on a quick island tour. We started at the spot where former Bounty Mutineers erected Fort George in 1789 to protect The Bounty from the local natives. There is nothing left of the fort today but a small plaque on the opposite side of the road. We continued on the cross-island path and saw the endless patches of agricultural plots, growing anything from cabbage to lychee.

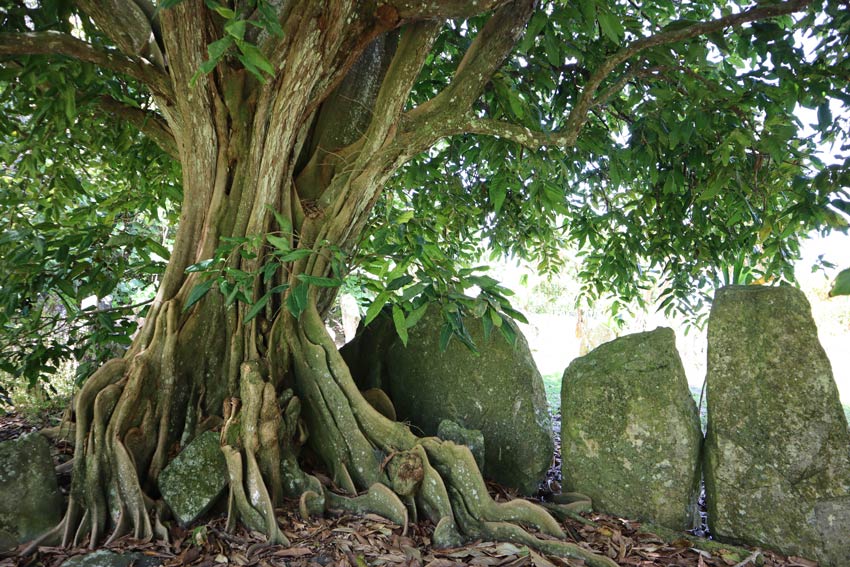

Wilson then took us further inland on foot to visit Marae Raitoru, an ancient Polynesian temple. It is one of 200 former marae discovered on Tubuai. Before entering the marae, Wilson instructed us to remain silent and to gather a small offering from the flowers and other lush fauna found at the entrance to the footpath. When called, each guest placed the offering at the base of the former altar, along with a postcard with our name written on it. We could also make a single wish to ask from the spirits.

This particular marae was used back in the day to celebrate a birth. It is here that the umbilical cord was cut in a ceremony and buried in the ground, over which a tree would be then planted. Wilson tells us that he often visits this marae in solitude and can feel the spirits of the marae’s former worshippers. Such stories are heard throughout the Polynesian islands and are a testament to the mana felt by so many Polynesians.

Hiking to the top of Tubuai

The sky was devoid of clouds the following day, a perfect opportunity to hike to the summit of Mount Taitaa (422m). Alone on the trail and also at the summit, the 360-degree views of Tubuai and its beautiful lagoon were thoroughly enjoyed.

Exiting the trail on the far side of the pension, I used the opportunity to further explore the island on foot, this time returning along the coastal route. There is hardly any traffic on the road, and this was a weekday. In the absence of any monumental highlights, Tubuai seems to be off the tourist path. From time to time, a rusty car passes by and greets hello. Every few hundred meters, I pass along another abandoned home or shop. Back at the pension, Wilson shares with me some of the hardships of living in Tubuai, especially after the cyclone. Many residents have simply left for Tahiti in search of a better life.

Motu Picnic

On the last day in Tubuai, I joined the other guests for a day on one of the motu lying at the edge of the coral reef. This geological feature is what sets the islands of French Polynesia apart from other tropical paradises. On the motu, you are completely detached from life, trapped between the ocean and the lagoon. On this day, the birds were celebrating, flying to and from the beach at rapid intervals.

As we made landfall, a fire was lit by Narii and his brother James, our hosts for the day from Pension Taitaa who runs these lagoon tours. Some of us were grating coconuts, some were emptying clams on the beach, and some were hanging around the fire with an early round of Hinano beer. As freshly-caught fish and coconut bread were tossed on the fire, we used the opportunity to get a local perspective on the hardships and the risk brought upon by the pandemic. With almost a complete cessation of tourism on an island that even in normal times doesn’t get too many visitors, locals have had to “return to their roots” and adapt to a more self-sustaining lifestyle.

After lunch and a nap, it was time to head underwater. Surprisingly, the coral around the motu was very impressive. It wasn’t the tropical fish that caught my attention on this outing, but rather the large clams with their intensely-colored lips. They seemed to be everywhere, perhaps even in our stomachs post-lunch. On the way back to the main islands, we made a challenging landfall on Motu One, a lonely sandbank floating in the lagoon. In a few decades, newly planted coconuts will perhaps turn this place into an ideal tropical escape but, for now, there’s nothing here but soft white sand unprotected from the waves.

Raivavae

The final stop in the Austral Islands was on the southernmost island in French Polynesia, which can be reached by plane. In fact, Raivavae only got its airport in 2002, so this island is still not geared for tourism, making it a perfect stop for those seeking to witness the Polynesia of old.

Raivavae is said to resemble the Bora Bora of 50 or 75 years ago. The 30 motu at the edge of its lagoon are still devoid of any form of absurdly expensive overwater bungalows. While researching ahead of the trip to choose which islands to visit on my fifth visit to French Polynesia, I read that Raivavae is a true undiscovered gem. I had no idea just how true the literature was.

Already on the approach to the runway, it is clear that something is special here. From the air, Raivavae is simply stunning and its immense lagoon radiates the shades of light blue that so attract me to this remote corner of the world. At the entrance to the terminal, there isn’t even the customary sanitary gel and we are instructed to wash our hands at the nearby hose.

I am greeted by Clarisse, owner of Pension Vaimano. It turns out that I am the only guest at the pension. Some local pensions are not welcoming international visitors but I am more than happy to be staying with Clarisse as her pension is situated on a hill overlooking motu piscine and its white sandbanks.

“G” is the new “R”

After settling into my bungalow, Clarisse offers to take me around the island. The name Raivavae means a sunny sky with no rain, and this is certainly the case on this bright day. However, Clarisse immediately corrects me and teaches me a very important lesson for any visitor coming to Raivavae. On this island, they replace “r’s” with “g’s” so Raivavae becomes Gaivavae, ia ora na (hello) becomes ia oga na, and māuruuru (thank you) becomes mauguugu. I was certain that this is a prank played on rookie outside visitors but after a few hours on the island, I came to an understanding that this is indeed part of the local dialect.

The island tour reveals just how different Raivavae is from other islands I’ve visited so far. The pace of life is practically at a standstill. Heck, you often even need to wait for pigs to cross the coastal road that hasn’t even been fully paved yet. In the absence of interior plains, nearly all of the local population of about 1,000 residents live along the coast. Raivavae seems to be an island that belongs in the Society Islands, some 700 km to the north.

Every house we pass has a canoe docked in the front, an elongated mailbox that’s actually used for delivering baguettes every morning, and a grave or two in front of the house. In the absence of a local cemetery, this is the norm in Raivavae, just like in Maupiti. I also notice that many families grow chickens and pigs in addition to the normal array of fruit trees. Clarisse tells me this is normal and that families must be as self-sufficient as possible. This is also the reason we see bananas soaking in the salty water of the lagoon. This “rapid ripening” method is used for feeding the livestock.

As we cruise along in her 4X4, Clarisse shares with me some of the ins and outs of living in Raivavae. Just like what I’ve heard in Rurutu, finding a suitable match on the island is a difficult task considering the small population and close blood ties between families. But that’s where your high school years come in handy as you head to Tahiti for that and hopefully use the time not only for getting a degree but also for finding a partner for life.

Clarisse shows me around the remains of a few ancient marae and she is very knowledgeable in the local history which helps me to vividly imagine what the religious ceremonies that took place here for centuries might have looked and sounded like.

We stop in the village of Anatonu with its whitewashed protestant church. Clarisse takes me to see canoe builders in live-action. The canoes of Raivavae are highly distinct as they are still only fashioned from local wood. No fiberglass here. Despite the new airport, the island seems to be successfully resisting modernity, and this is another testament to that. We wrapped up the island tour with a visit to the only remaining tiki statue on the island. Apart from the Marquesas Islands, it is quite rare to find ancient religious statues in Polynesia following the swift and successful conversion by Christian missionaries back in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

Climbing Mount Hiro

The highlight of my visit to Ravaivave was undoubtedly hiking to the summit of Mount Hiro (437m). Using ropes tied to trees and fighting my way through thorny bushes, I completed the short but steep ascent to the ridgeline, where the entire island was now at my feet. Continuing along the narrow path, it was a short distance to get to the very top of the island.

The hike to Mount Hiro is one of the best hikes in French Polynesia. There was no one else to share the beauty of this place with me but that was just fine. From the summit, the colors and sounds are mesmerizing. The lagoon frequently changes colors with every passing cloud, birds ride thermals up and down the steep cliff, sometimes even diving to catch prey as if they’re kamikaze. Raivavae is truly an unspoiled and yet-to-be-discovered gem!

Motu Piscine

The final act in Raivavae was a trip to Motu Piscine which translates to “swimming pool islet”. The name is very fitting as this place is simply straight out of a postcard. Catching a boat to the motu is something that needs to be arranged and you can even stay here for a few days in a cabin. As you would expect, the sand is oh so white and the water is as clear as glass.

Sad to leave but also looking forward to returning to French Polynesia’s “Manhattan” after over a week in the remote archipelago, I met an elderly woman waiting for the flight to Tahiti. She returned to Raivavae after many years in Tahiti to visit her father who, at the age of 94, is the oldest living person on the island. She was showered in flower and shell necklaces from well-wishers to the point that she could hardly stand. Clarisse tells me due to the woman’s own age, it is unlikely that she’ll ever return to the island and that this may be the last time her friends and relatives will see her. Such is life in a nation of isolated paradises. You must always leave an entire world behind. Polynesians must be good at goodbyes, but I am not.

What’s Next?

In the next post, we’ll head north, as close to the equator as possible, and visit the Marquesas Islands. These majestic islands are wild in all respects and for history and nature lovers, it is an overwhelming experience.

>> Read the next post from the Marquesas Islands >>

Heading to French Polynesia? In-depth island guides to all 5 archipelagos await you, including sample itineraries and essential travel tips & tricks.

Tahiti, Tailor Made!

The Islands of Tahiti are among the last places to be colonized by mankind, 118 islands, each with its unique personality.

Get expert advice and assistance with planning your trip to the destination where tropical dreams come true!